What Will Last When Everything Vanishes?

VIKRAM IYENGAR

Read this FIRST, not last

Learning, life experience, knowledge, wisdom, memory… where does all this live? As dancers, we don’t (hopefully) see, experience, and perhaps even understand the body and mind as separate entities. Perhaps even the soul and spirit (defined as we individually prefer) are part of this holistic being. We literally embody knowledge – we ‘know’ in our bones; our muscles are carriers of emotions, our flesh and skin imbibe and transmit information. The mind inhabits every pore of this body, and the experience of the body permeates thought, action, remembrance, and communication. This is how we live and possibly how we die. But sometimes the mental and the physical seem divided. Sometimes, one of them remembers while the other forgets. Sometimes how we live ruptures from how we die.

Watching my mother’s journey through and with Alzheimer’s Disease – as a son, a primary care-giver, and a dancer – I note the dramatic changes and shifts in physical, psychological, cognitive, and mental expression and ability over time. Sometimes gradual, sometimes precipitant – always in a downward spiral. Sometimes recognisable as coming from the person I know / knew as my mother, sometimes absolutely not. Identity and relationships are thrown into constant and often tumultuous flux, both for her and for those around her. Body/mind, self/other, fact/fiction, memory/illusion, past/present, here/there are all in conflict – a conflict that constantly shifts relationships within itself. Until – strangely – everything settles again, so we can repeat the question - Learning, life experience, knowledge, wisdom, memory… where does all this live? And (how) does all this die?

Last(ing) Lessons

There is something that can’t quite be classified so easily under the physical, psychological, cognitive and mental – it can’t be classified under expression or ability either. It has to do with pure existence - the way one inhabits time and space, affects them both while being (perhaps) affected by them in turn. It has to do with shining brighter as one inexorably fades away; it has to do with presence-in-absence, with arrivals and departures, with unbecoming. It is – it must be – a strange, unsettling journey to what is often described (inadequately) as regressing to a child-like state. It is inadequate because that state lacks the quintessential child-like quality to learn – and remember.

Or perhaps not. Perhaps my mother is learning – learning to forget.

-

Ma hails a taxi to go home – something she has never done by herself before, so that in itself is unusual. She says – PNB, Salt Lake. This is a landmark 5 minutes from home that all taxi drivers know. Once there, she is lost, disoriented – she cannot recall the address, the directions. She is recognised and rescued by a neighbour.

Ma Journal, 3 August 2021

-

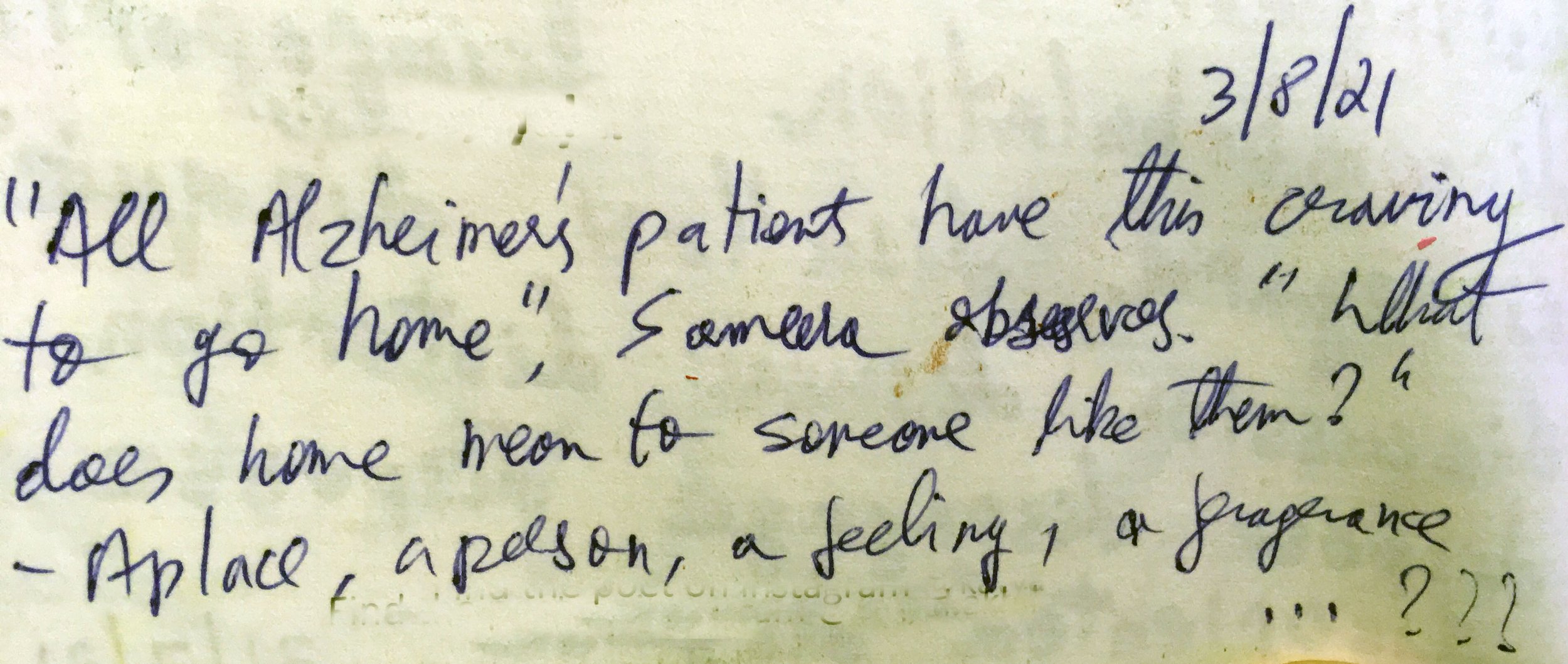

Ma is in Mumbai with my sister. I am in Delhi on work. Ma calls me to say that she has received a call from home asking when she will be back. Who is looking after this house while we are all away, she asks? This ‘home’ is not Calcutta, I gather. Is this one of her childhood homes up in the hills of Assam and Meghalaya, I wonder? Is it, was it real – or is it something between reality and imagination, the world of neither here nor there that she enters and leaves regularly now? How do I tell her that no such home exists, when she is so obviously seeking an anchor to cling on to?

When we are back home in Calcutta, she regularly asks – when are we going home? Soon, we keep telling her. Until one day she says to me – ei bari tao toh khub shundor. amra ekhanei thakte pari [this house is also beautiful, we can stay here]. Has the image of the home she is hankering for become too faded for her to access? Has she returned to recognising our home in Calcutta as hers? Or is this her way of making peace with a fraying memory that she probably knows is playing tricks on her?

-

In my first conversation with him, Dr. M advises me to think about it from her point of view, her knowing that she is forgetting, that blanks are appearing in her life that she cannot fill. How terrifying an experience that must be – of feeling oneself slowly disappearing into oblivion while still capable, cognisant, and conscious. How can we who remember – or, at least, remember differently – support her on this inconceivable journey from remembering to forgetting? And then let her go?

Ma Journal, 25 December 2021

KD called today to wish us [happy new year] and asked after Ma. I asked Ma – do you remember KD? Without hesitation, she said – of course! Deep connections, quiet friendships – can these really disappear so easily?

Ma Journal, 31 December 2021

Vikram

Biktam

Viktam

Bikram

She suddenly calls out my name from her regular morning seat at my window. I go to her, ask her what she wants. But I’m not sure she registers me – or ME as Vikram. She holds my hand, and repeats the sound of my name. It is heavy in her mouth – the familiar become unfamiliar. She moves the word around with her tongue – feeling it anew, cherishing the sound – it seems to give her peace, calmness. Having now found it, she releases the name again.

Ma Journal, 25 February 2022

-

Ma begins to have difficulty swallowing, and now requires regular swallow therapy to remind the muscles to do what they have done practically involuntarily for eight decades. A couple of years ago, I told my sister – she still remembers clearly how to wear a sari by herself. My sister said – her body remembers. But now her body has begun to forget too: how to move, how to speak, how to swallow… Or is it that she is imagining the action, but no longer able to perform it?

-

Ma hardly ever speaks now. But sometimes as she gazes at me, her mouth works. It seems she is trying to say something. The words come forth in her sleep. Her dream world is a place where her body loses its current limitations – she is free there. Sometimes – just sometimes – this liminal lucidity visits her when she is awake. Words suddenly break through, responses suddenly become clear. She nods, she sees, she appreciates, she communicates. But this is merely a window, before she recedes again behind a mist.

It was such a gift to see you emerge like you did today – present, interactive, curious, interested. Your eyes were bright and alive. They took in people, responded to them, watched the road, the trees, passers-by avidly. You sat straight in the wheelchair, your hands reached out to us to hand us things, ask for things – reached out to the balcony railing to help you stand… You did not want to go back to your room. Once there, you spoke clearly, sensibly. Answering, commenting, interacting. Your eyes still bright and alive with intelligence – they were YOUR eyes after a long time. But they had a shadow of confusion – as if they had awoken after a long sleep and could not quite recognise what was around them. Perhaps you wanted to drink this in more, perhaps that’s why you did not want to succumb to sleep.

Ma Journal, 8 September 2022

How do you choreograph forgetfulness – and remember the moves?

As dancers, remembering choreography is a skill we are trained in. It is one of our core strengths, this ability to recall. And if we are able to recall and repeat with freshness, that’s an added bonus. Even when improvising, the body remembers technique, it remembers in flesh, blood and bone how to ‘do’. Forgetting, for us, is an embarrassing trait – we are trained to remember. Forgetting makes us vulnerable and fragile in ways we do not want to be. The body and the rigourous training we instil in it, is all we dancers have (or is it?).

-

Ballet and contemporary dance trained Anika Bendel and kathak trained me have devised a project – Imagining Improvisation: improvisation techniques in classical dance. This has emerged from us bartering our different trainings with each other on the sidelines of another project. We became interested in exploring what exactly is meant by improvisation in two very different so-called classical traditions – ballet and kathak; and if and how structures and systems applied in one could work at all for the other. In a two-week residency in Calcutta, we are working with six kathak dancers looking specifically at two techniques for creating choreography that have emerged directly from ballet – Willian Forsythe’s Improvisation Technologies and Amanda Miller’s Nine-Point System.

No – they don’t work for kathak in the way they are conceived (surprise, surprise!), and will need major modifications in how they see the dancing body, and therefore what they ask of the improviser, before they can be of any use to kathak-trained dancers. For example, both systems are constructed to push dancers to work with extensions in all directions. It works for how ballet is conceived, with movement floating away from a centre. Not so with kathak, where movement curls back on itself towards a centre. So how movement improvisation is visualised and enabled is fed directly by a certain and contextual experience, knowledge, and perception of the moving body, and what it is (supposed to be) able to do. Though not trained in contemporary dance, I would venture to say that this holds true there too. What the improviser is trained in, what their body ‘knows’ directs how they journey into the unknown through the process of improvisation. Imagination needs an anchor, and here that is the memory that the body carries within itself.

“You must learn the technique so that you can forget it when you perform”

[Paraphrased from my memory of a comment by Odishi dance exponent Sanjukta Panigrahi at a lecture-demonstration in Delhi, early 1990s.]

The concept of the ballet body and the concept of the kathak body are markedly different as are the principles of movement, expression and improvisation the two forms are based on. It is these deeper, more essential differences rather than the surface similarities that are more interesting for the workshop conductors. It is here that the participants will face the tensions of opposing understandings of the body, movement and space assumptions, dynamics and essence of dance itself. It is also here that the appropriateness of improvisation techniques will be tested to the extreme – tested, abandoned, modified, evolved, redefined. Therefore, it is here that the participants will discover the most about themselves, about each other, and about the two forms through a creative, often contradictory, dialogue.

Excerpt from the ‘Imagining Improvisation’ research proposal

I’ve been working with Australian director and dramaturg Sally Blackwood on a creative development called The Aesthetics of Ageing, drawing from our experiences of caring for our parents (her father, my mother). One of my movement improvisations responded to specific physical images that we had talked about. When watching it, at a certain point Sally remarked on moments where she suddenly saw an able-bodied dancer rather than a physical fragility. So how do we learn not to (or learn to forget to) draw on our dancerly strengths, and yet use the physical ability of our strong, controlled and trained bodies to communicate physical fragility?

In Get a Revolver, [Helena] Waldmann explores forgetting as a positive, liberating function of the human brain, sensing that the secret to happiness might lie there. With the superb dancer Brit Rodemund, she has created a grotesque yet humorous work, a reflection on restraints and the efforts to overcome them, using ballet as a symbol for the rigours that life demands of us. During the 60 minutes of the performance Brit Rodemund becomes her own twin – a classical ballerina with dazzling presence, and then a searcher for whom everything, even her own body or a plastic bag, is a source of wonder.

(Stuttgarter Nachrichten, Stuttgart, Germany, as quoted on https://www.dansedanse.ca/en/helena-waldmann-get-revolver)

The wonder of first times/ wondering about last times/ wandering in time

-

I don’t recall the exact date. It is afternoon, and I step into the foyer of the Kala Mandir auditorium in Calcutta holding my mother’s hand. I am all of 6 years old, and I am going to perform in Navarasamalika – a mammoth production choreographed by my guru, Smt. Rani Karnaa. It is my first time on stage, and I say to my mother – ‘bhoy korche’ (I’m scared). It’s a clear memory – as clear as a memory can be tinted through the glass of time. I even remember that I’m wearing a black (or was it navy blue?) kurta.

The first time on stage – like first times of anything – is special. And forty years down the line – now as professional performance makers – that has moved into stories about the last time we performed: ‘last’ as in ‘previous’, not as in ‘final’. How would we know when it was the last-as-in-final time that we have the ability to do something, move a certain way, speak, sing, dance? And – if we had that knowledge by some miraculous and daunting insight – how would that change how and why we ‘do’ it? How would it change our relationships with our own bodies, with the people and objects around us? And (how) would we remember them? How do you notice a ‘last time’ approaching? And is a ‘first time’ always easily identifiable?

I try and recall the first time Ma noticed something was amiss / we noticed something was amiss with Ma? It’s not so simple to pin down. There are many first times that only become cumulatively clear in hindsight. With a creeping and silent disease like hers, the early symptoms are so easy to miss, ignore, adjust to, and navigate through – even for the one experiencing the onset of the disease. We all do this unconsciously, subconsciously – automatic pilot kicks in. The truth is unthinkable, unimaginable.

I did not think at first that I could live through it. Music is the heart of my life. For me, of all people to be betrayed by my own ears was unbearable.

At first, I did not realise anything was wrong, though people seemed to be mumbling a lot, especially on the phone, and I began to sense that I was using a heavier touch on the keyboard. I wondered once or twice why I did not hear the birds sing so often, but assumed that that year we were having a quieter spring. I wasn’t playing with other musicians at the time, so catching my cues was not an issue. And when I listened to music I simply turned the volume up.

It was probably getting more difficult for me to hear the piano, but so much of what one hears is in the mind and the fingers anyway. The truth of it is that I don’t think I understood what was happening. How could I imagine that I was going deaf in my twenties!

Vikram Seth, ‘An Equal Music’, p. 150

For dancers / performers our extensive training supports our physically demanding practice, but can also create habits that allow us to negotiate through a performance on autopilot – we come to know it so well. And that can make us (and the performance) jaded. I once had a young actor tell me he had had enough of a role after the premiere run of merely five performances, and that he was bored with it. He needed something new, something that he would be doing for the first time again. While this works in the world of film where a performer delivers a role just once, this is completely impractical and impossible in live performance – whether dance or theatre. So how does one communicate a first-time-ness or a last-time-ness through the body in performance? Are the two necessarily mutually exclusive? How do we insist on a here and now, every single time we perform – even if we know it will be the last time?

I entered the project with a kathak trained body. Indeed, this training – now second nature more than anything else – is the core of the piece. Not just in terms of technique, but also in terms of aesthetics, approaches, taboos, and exclusions – what does not get trained, knowingly or unknowingly. The vertical stance of kathak is unique in Indian classical dances. But the very first question I encountered was – what does it mean to be vertical? What is the body aware of? And what is it not aware of? Our daily sessions of intense physical training introduced me to ideas of alignment, minute body awareness, core muscle control, and a lengthening of the spine (and therefore the body) which I had not encountered before. Bringing these into a bodily muscle memory through constant correction and repetition took me back to what it must have been like when I first started learning kathak. At that point, one becomes gradually aware of everything since it is not ‘natural’ to the body. Second nature takes a while to emerge and take over. And there lies both the achievement and danger: it becomes easier, it becomes natural, but it also becomes more and more difficult to pinpoint, articulate and remember all the tiny details every time one performs it.

Excerpt from my interim report on the process of making ‘Across, not Over’

-

Preethi Athreya (choreographer of Across, not Over) and I have isolated where the root of the very subtle kathak torso movements lie – the small of the upper back. And we have dispensed with any accompanying arm movements to try and deconstruct – then construct - phrases of movement using solely this tiny source. We’ve generated a series, which I am playing with. There is some sort of order, but I am following the kathak improvisatory habit of choosing and playing in the moment: therefore exact repetition is not really possible, and I am often surprising myself. Preethi finds something amiss – the mind seems too taken up with the act of choosing (and then enjoying the choice) to actually fully invest in fleshing out each movement itself. And, consequently, there is a certain restlessness in the air coming from a mind hopping about, albeit playfully; and a body not fully prepared to meet the next movement it encounters. This is quite the opposite texture to the sense of expansive calm and quietness that we are aiming for.

Preethi asks me to create, memorise and strictly follow a score. 8 sets of 8 counts over which the movements are laid, with precise counts to begin and end on – so what is staccato, what is fluid, what follows or emerges from what, what is long, what is short is all pre-decided. Improvisation – at least in performance – is denied. By extension, then, the enjoyment that accompanies improvisatory play must also disappear. But as I structure and restructure the score with Preethi, memorise, forget and – yes – slip into improvisation that is immediately recognizable as a hiccup in carefully thought out pattern, I find I am indeed able to more deeply inhabit the movement. I am able to commit to it, invest in it, and believe in it like never before. Because everything else is – in a sense – constrained into a predetermined progression that demands utmost specificity from me, I find I am able to relish every moment in every movement, travelling through them with a sense of personal discovery and sensorial enjoyment each and every time.

-

[I write this on 24 September 2022, the day after Roger Federer’s emotionally charged last game that announced his retirement from professional tennis. It was also the day Jhulan Goswami retired from professional cricket, but with far less fanfare and coverage.]

My friends and I are watching the American Ballet Theatre’s production of Giselle in New York. It is acclaimed Argentinian prima ballerina Paloma Herrera’s farewell performance: she is now 40, and she is retiring from performance at the professional level. She has been with the company many years by now. Her performance is astonishing: her technique, her grace, her pointe perfection… she is a ‘girl’ on stage, just as ballet always demands of a ballerina – no matter if this is her last performance before retirement.

What is more amazing is the performance post the performance. I expect a standing ovation that will last perhaps a little longer given that it is her farewell performance. But I am not prepared for the grand emotional and reverential display that follows the official curtain call. A standing ovation of more than 20 minutes, an unending line of people coming up with bouquets that are then laid at her feet as the bringer hugs her or bows before her like a devotee, the single white roses that are added to this growing heap of flowers by each member of the corps de ballet, the confetti that begins to rain down on stage, the shouts from the audience, and the flowers that are flung onto stage from the house… I don’t know what to think or feel. It is overwhelming, this love and respect that is being showered on a dancer. I envy it a bit, wondering if anything similar could ever happen in India. But I am also acutely aware of the ballet hierarchies that this display reinforces, where a performance of respect is expected – much like our classical dance world perhaps.

However, I am most struck by this concept of ‘retiring’ from dance at a professional performance level. I can’t think of any parallel in the Indian context. Age is revered – though how much of this reverence is also a performance is a question that must be asked. And this reverence often keeps dancers who can no longer dance centerstage, making more and more excuses for a frail body that can no longer do the things it was trained to do. Age is revered in our context – but the limitations that age brings are not accepted with any kind of grace. A friend recently told me about watching Mikhail Baryshnikov dancing live in front of an older film of his performance of the same piece (was it Le Spectre de la Rose ?). Now in his 70s, he matched a bit of it step to step, but then stood aside when his younger film-self launched into technical wizardry that was no longer possible for him. My friend said it was such a poignant moment to see him accept his body in the here and now. On the other hand, I recall bharatnatyam dancer Yamini Krishnamurthy – now 80+ - laughingly responding to a question during a lecture demonstration in St. Stephen’s College, Delhi (1995) about how old people are depicted in classical dance: “we dancers never get old”, she said. So – in dance as in life – (how) do we know when to call it quits?

An object had to justify its being to itself rather than to the surroundings which were foreign to it. [By doing so, the object] revealed its own existence. And when its function was imposed on it, this act was seen as if it were happening for the first time since the moment of creation. In The Return of Odysseus [1944], Penelope, sitting on a kitchen chair, performed the act of being “seated” as a human act happening for the first time. The [physical] object acquired its historical, philosophical, and artistic function. (Lesson 1)

[quoted in Kobialka, Michal. “‘The Milano Lessons’ by Tadeusz Kantor: Introduction.” TDR (1988-), vol. 35, no. 4, 1991, pp. 136–47, https://doi.org/10.2307/1146169]

It’s called the long goodbye. Rapidly shrinking brain is how a doctor described it. As the patient’s brain slowly dies, they change physically and eventually forget who their loved ones are and become less themselves.

Excerpt from a Facebook post on Alzheimer’s Disease by my friend UAC, 9 January 2022

I’m learning to redefine everyday what memory, recognition, and love are and where they live in a person, because while my mother moves further away from us, she is also – in a strange way – drawing us close to her.

It’s not a disease – it is one of the ways our bodies age and prepare for departure.

Excerpt from my response to UAC, 9 January 2022

Do we even know how and where memory is stored in the body?

What about memory and its relationship to trust?

If I am a product of my environment and experience, it’s all to do with my memory of that. What happens if that is suddenly gone? If that disappears, who or what am I?

If the past is unreliable, the present is unsure…

‘The Aesthetics of Ageing’ notes, 22 December 2021

My mother’s experience of life currently is only of the here and now – no past, and no idea of the future. So is everything she does being experienced for the first time and / or the last time? But she still ‘knows’ how to lift her hand, how to hold onto or release an object, how to turn her head, how to open and move her eyes, how to swallow – and yet she doesn’t, the muscles have to be constantly reminded, cajoled into remembering. Sometimes they recall, sometimes they don’t. There is no past, so there can be no cumulative learning in this process of doing, forgetting, reminding, and forgetting again. Where indeed, does memory live in the body when the so-called cognitive, conscious mind has forgotten it? When is / will be the last time one remembers?

On what would turn out to be Katie’s last good day

she asked to be wheeled outside & helped

into the Lazyboy her brother dragged out back

no one even bothering to remove the tag

from Costco that flapped, wild as a trapped bird

before the wind surrendered

to a thin cardigan of mid-December sun

as all afternoon we watched

her sleeping while the sky hemorrhaged

quietly down & the small hills of dogshit

arranged along the graying cedar fence

did not blaze into anything

like golden stones, but her hair had grown

back a half inch or so & so glowed

in the last of that tinny glare

& if I thought briefly then of medieval manuscripts

where everyone important grows a halo

it wasn't quite like that either

although the bones of her face did appear

as if at low tide to surface

smooth as driftwood where the injured

bird might light in the moonlight, holding on

for some measures longer than expected.

‘Late Fermata’, Jenny Brown

25 December 2021

Before she goes to bed, Ma spends some time in my room doodling and listening to Kanika Bandopadhyay’s Rabindrasangeet. She joins in once with the title line of Amar Mallika-bone with the perfect pitch she and her sisters have. She has not sung since. Is / was that the last time?

Yes, that was. That will be. That is. Though I did not know it then.

How long does time last?

-

As part of our discussions during The Aesthetics of Ageing creative development, I’m talking to Sally about what it feels like to spend time with my mother in her condition. “Time stops, relaxes and extends” – that’s the phrase Sally notes down and offers back to me as an impulse to create something from. I tell her about my image of the lake.

In some long-forgotten episode of The X Files, Dana Scully is in a coma. Her condition is illustrated through a metaphorical image: she sits in a boat in the middle of a lake with people speaking to her from the banks. They cannot reach her, but she can row to them if and when she desires or can. Often, this is how I see Ma. What does it mean to exist and float in this vacuum? Is it a gathering darkness she feels, or is she in a realm of light we can neither enter nor comprehend? When is she NOWHERE, and when is she NOW HERE?

To the music of Eric Satie (and later Jody Talbot), I create my response to Sally’s impulse drawing on the image of floating in a lake. How does the body float, how does it exist in limbo? And how does one give a sense of fluid water on solid ground?

A vertical body just about balanced on the balls of both feet.

A slow to and fro rocking motion which occurs only in the feet with the rest of the body tilting accordingly.

A piece of cloth held in one hand that goes under both feet, controlling the body’s motion like a rudder.

Gradually the body starts to pivot, with the same motion in the feet.

A durational timelessness.

A weightless, yet anchored body – here, but far away.

A cyclical, repetitive movement that shifts fluidly and invisibly like currents within water, and yet remains still and silent.

Time pauses, but does not stagnate. It roots itself and drills deep. From a moment of experience that is constantly relived, re-experienced, re-expressed, it becomes a world to inhabit.

28 September 2022

My sister posts on Facebook marking two months of our father’s passing: Time flies / Time Hardly Moves – she says. And I think of the memories that social media reminds us of repeatedly – what we did, who we were with, the friends we made on this day last year or several years ago. A barrage of images that we may or may not want to recall – we no longer seem to have a choice in that. I remember my mother this time last year – memory affected, but still able to talk, walk, eat, comprehend, communicate: overturned in the space, in the time of a year (though it seems like an eon ago). And I think of the nature of time – how it can rush, how it can stand still, how it can pause, how it can repeat itself, how it can (can it?) go backwards… is it the nature of time or the nature of how we experience time? Is time linear, or not? The jury is still out on that one, I think.

The Restaurant at the End of the Universe is one of the most extraordinary ventures in the entire history of catering.

It is built on the fragmented remains of an eventually ruined planet which is enclosed in a vast time bubble and projected forward in time to the precise moment of the End of the Universe.

This is, many would say, impossible.

In it, guests take their places at table and eat sumptuous meals whilst watching the whole of creation explode around them.

This, many would say, is equally impossible.

You can arrive for any sitting you like without prior reservation because you can book retrospectively, as it were when you return to your own time.

This is, many would now insist, absolutely impossible.

At the Restaurant you can meet and dine with a fascinating cross-section of the entire population of space and time.

This, it can be explained patiently, is also impossible.

You can visit it as many times as you like and be sure of never meeting yourself, because of the embarrassment this usually causes.

This, even if the rest were true, which is isn’t, is patently impossible, say the doubters.

All you have to do is deposit one penny in a savings account in your own era, and when you arrive at the End of Time, the operation of compound interest means that the fabulous cost of your meal has been paid for.

This, many claim, is not merely impossible but clearly insane…

Douglas Adams, ‘The Restaurant at the End of the Universe’, p. 80-81.

To be still in motion, to move with stillness – Time has quintessentially dancerly qualities. And when thinking of time – as a dancer – I can’t help thinking of space too. The same questions… what space / what time does space inhabit? And what is my place within that? Memory is about space as well – seeing something across time, and across space. Remembering both the where and the when. And noticing the tricks our minds play on us.

When my mother was still able to remember (after a fashion), she recalled her younger sister only as a child, and could not / would not believe that she was now a grandmother. She moved between times and periods as we move between rooms, with an un/easy ability to inhabit more than one such simultaneously. Right now, though – time for her seems to have paused indefinitely as she exists in the same moment – moment after moment – trapped in her body, in her hospital bed. And as she goes through cycles of marginally different better and worse days, drifting in and out of worlds, we give her the comfort we can (or is it ourselves that we are comforting?). All the while we wonder, how long will this limbo last – and why?

“We are now in the departure lounge”, once quipped my mother’s dear friend referring to their advancing age. “We are all in the departure lounge, even if we are ten years old”, laughed another much older friend of mine recently.

Passengers are to be kept in temporarily suspended animation, for their comfort and convenience. Coffee and biscuits are served every year, after which passengers are returned to suspended animation for their continued comfort and convenience. Departures will take place when the flight stores are complete.

Douglas Adams, ‘The Restaurant at the End of the Universe’, p. 70

-

I am revisiting and rechoreographing a 2003 production – Shunya Se. Going back in time to go forward so to speak. The piece is inspired by the five elements, and I spend an inordinate amount of time on re-envisioning the section on Space. I find myself designing choreographic ideas through metronomic time – I am measuring out time in order to demarcate space. All my notes on movement refer to a repeating cycle of 28 beats – 4 sets of 7 beats. And the opening sequence is literally a dance of relational speeds of walking against the fabric of a 56 bpm metronome – single, double, three times, one-and-half… The play is between bodies moving through the same walk at different paces – the tension when they are not quite together but obviously in a patterned relationship, and the release of that tension when – quite suddenly, and just for a moment – they come together. “It had a sense of time stopping’, said an audience member after the performance.

I transfer this choreographic score to an excel sheet, and hand it to the music composer who has been sitting in on some rehearsals. He is delighted – this notation of time rather than space gives him a clear musical structure to create from and for. One glance tells you what each dancer is doing on any single beat. Ironically, the dancers find the excel sheet extremely difficult to read, though it pins down moments of the ensemble coming together and moving apart far more effectively than their individual notes.

This propensity to start with rhythmic structure comes naturally to a kathak trained dancer. Training in the taal system is the first thing we are introduced to. Taal – cyclical rhythm structures on which we layer speeds of footwork; that is drummed into us so that in performance we can enjoy and offer – as Dr. S. K. Saxena says in ‘Swinging Syllables’ – “the delight of being able to toy adroitly with rhythm”. The taals are varied, and of various durations – 16, 14, 13, 15, 10, 9, 12, 18 beats … Each has a different structure of counting and beat stresses, and each beat has a name, an identity giving each taal a unique flavor. So to say 14 beats is not enough – is it 14 Dhamar, 14 Ada Chautal, 14 Deepchandi… Each one sounds different to drum out on the tabla / pakhawaj or to speak in bols (mnemonic syllables). The bols lay out the space the taal occupies, and the space divisions are not consistent or regular (though the time divisions are). Each beat can have a single or multisyllable name – or even be mute / un-named. So while the cycle lays out a regular larger time-space, each beat has time-spaces within itself depending on how slowly or quickly one must say its name within the fraction of time that beat exists before passing on to the next one. And yet, the overall space-time of each cycle remains constant.

Over time (!) I have come to think of the kathak virtuosity of punctuating with and within these rhythm structures as filling the spaces of time, so that the aural and visual experience of beats comes alive – compressing, expanding, circling in on itself, standing still. But always on the way to somewhere, when you can finally say with pointed precision –

H e r e ! I am now here!

Extracts from my ‘Shunya Se’ notebook

The excel score for Space - snapshot

For us dancers, isolating each muscle, each part of the body to enable us to create extremely specific and directed movement is a matter of rigorous training. For my mother – in her incapacitated, broken, failing body – to move her right hand an inch, to open her palm, to clasp my finger is nothing short of a supreme act of will that spans a time-space that I cannot comprehend. It states / queries –

Here I Am –

(am I here?)

H E R E I A M N O W H E R E

She was not exactly waiting, she felt. No one else she knew had her knack of keeping still, without even a book on her lap, of moving gently through her thoughts, as one might explore a new garden. She had learned her patience through years of side-stepping migraine. Fretting, concentrated thought, reading, looking, wanting – all were to be avoided in favour of a slow drift of association, while the minutes accumulated like banked snow and the silence deepened around her.

Ian McEwan, ‘Atonement’, Pg. 150

Self Gathering

A pause that remembers

What is yet to come

Sampurna Chattarji, ‘Self Gathering’

A presence of absence / an absent presence / the present is absent

There is a bitter-sweetness when Ma surfaces from the world she inhabits. There is a slight, gentle confusion in the eyes – and a sense that she is seeing things from far away – seeing them crumble. The sand is running through her fingers. She is not watching life flash past, she is watching it drain away.

But in that moment that she recognizes loss and losing, she also recognizes us, holds and clings on to us.

Her eyes are far away. She seems to be waiting, preparing for her next departure – but she has chosen to wait with me. That has to be enough.

Ma Journal, 30 August 2021

What is this mysterious thing we performers call presence? Who has it, who doesn’t? How can one create it, share it? When is it conspicuous by its absence? And when is the performative presence created precisely through absence? What is it that makes a performer compelling to watch?

The performer acquires primacy when she cultivates a qualitatively different presence on stage from that of daily life, a presence which has an enhanced energy and an enhanced consciousness. […] Energy becomes consciousness when it moves from the physical to the psychological realm. The actor must expand her inner focus progressively to increase her inner awareness. This is not done so that the performer can bring a kind of Stanislavskian psychologism to her performance, but because it enables her to bring a concentrated, multi-layered simultaneity of consciousness to her performance. A quality of ‘hereness’.

Veenapani Chawla, ‘Space and the Actor’, The Theatre of Veenapani Chawla, p. 118-119

Playing with Marcello was like nothing else I have experienced in life. Particularly when we had no idea what we were doing.

He was at his most brilliant with the unforeseen, the unknowable, the chaotic, with what was invented on and in the moment.

To be able to do that you have to be here. To be as present as a fox, as quick as a rat and as agile as a fish. He was so utterly present. Always. So utterly present was he, that now I cannot refer to him in the past. I cannot conceive of him in the past at all. It feels impossible. He is here. Somewhere. Just around the corner. Ready for the unforeseen. The unknowable. Ready to play so freely. So lightly. So free. He is here somewhere.

"Ariel", calls Prospero in his penultimate speech "… to the elements Be free…" Yes. He is still somewhere here. So free.

Simon McBurney’s tribute to performance maker Marcello Magni, on his passing, Complicite emailer, 20 September 2022

-

I’m an MA student at the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies in what is now the University of Aberystwyth (then, the University of Wales, Aberystwyth). Every Wednesday at the Arts Centre Studio, there is a PIP – Performance in Practice – session. It’s basically a group of performance faculty and students leading and sharing practice with and for each other. One such session is led by my professor, Richard Gough. He shares an exercise devised by Pina Bausch.

A chair in the middle of the room.

Someone sits on it –

everyone else watches.

The task is simple – in the fullness of that multiple gaze, make yourself disappear.

And this sends me to another memory from 1998 or 1999. Towards writing a piece for the Seagull Theatre Quarterly, I am observing a workshop for school students conducted by the playwright and director Mahesh Dattani. He is asking the group to walk around the space, and then pause and respond to an instruction – all beginning with the active verb ‘Do’. One of them – and the resultant bewilderment – remains clear in my mind.

“Do Nothing”.

-

I’m working with Preethi Athreya on what will become Across, not Over – a solo choreographed by her for and with me. We’re working on precisely locating and zooming in on small bits of movement in my kathak-trained body, movements and movement principles that come very much from kathak. But she is asking me to drill down into them, focus into an origin point that is deep within the body. The muscles in the upper back, for example. So specific, so small, so at-the-other-end-of-the-spectrum from the expansive kathak arm movements that they actually give rise to. So quiet.

How - when they are situated so deep within the body – do these tiny movements and muscles claim their own independent presence, against and within the canvas of the whole body that is so gloriously visible? “What do you want the audience to see”, Preethi asks. “Breathe into that, and quieten everything else.”

Quietness, stillness, hereness … the ability of a dancer to not move, but still dance. And compel an audience to watch.

I have seen your mother once. I did not know in the beginning that she is your mother , but I remember her magnetic personality, her grace , her intelligent eyes and her bindi .

And she has such a presence , I remember looking at her multiple times.

A response to a Facebook post by my sister carrying a photograph of our mother

-

Auditions are on for Helena Waldmann’s production Made in Bangladesh, on which I am co-choreographer. In marked contrast to my work with Preethi, Helena plans to draw on the explosive, flamboyant and virtuosic aspects of kathak as tools for the narrative of constant production and over-exploitation that she wishes to weave. So we’ve been looking for and testing kathak technique in these auditions. Thus far. Now Helena is looking for something else as well. The task for the improvisation is again deceptively simple: make yourself invisible.

No one quite knows what to do. What does one deliver? What technique does one show? What capacity are they being asked to prove as performers? People try various things: one person hides behind a billowing curtain, another illustrates disappearing through hopelessly visible movement, some just dance without really interpreting the instruction. One dancer sits in the middle of the floor, looking around for a bit, confused, utterly bereft of an idea. She ultimately lays her forehead on her knee, deciding to not offer a response. And in the plethora of the movement and activity and attempts to vanish around her, she quietly disappears while remaining in full view, peeling our eyes away from everything else to the void she both creates and inhabits.

We see her invisible.

She says clearly, quietly and firmly, “I am (not) here.”

To be here, and to not be here as well – in the world of performance, it is perhaps puppeteers who embody this most clearly, as their practice is based fundamentally on breathing life into inanimate objects and making themselves (the givers of this life) disappear. They disappear sometimes literally behind screens or puppet stages that reveal only the puppets. Or – like Bunraku puppeteers – they remain fully visible to audiences, and yet direct their and our full attention into the puppets (or objects) that become people and characters. And it can happen anywhere, with anything. Dadi Pudumjee in a lecture demonstration in Bhopal (1998) covered his hand with a dupatta, and before our eyes there was a woman peeping out from under her veil; Anurupa Roy visiting my workspace in Calcutta (who knows when!) carrying her Bunraku character Gul Badan, and effortlessly making her a living, interacting part of our conversation. And then seeing Anurupa’s About Ram in performance, that adapts the Bunraku technique to Indian movement to make us believe in the puppet Ram even as we are un/able to invisibilise the three handlers who breathe life into him.

For we have a multiple consciousness, or diversified spaces within us, each possessing a different quality and degree of subtlety, often pulling in different directions. We conveniently cover all these spaces under the blanket of ‘mind’, to provide a cohesion or homogeneity to these differing movements within us. We flow from one space to the other like water without control; and sometimes, like water, we are in all the spaces simultaneously, but in a kind of haze. The conscious, energized performer will, through a daily practice of self-observation, bring to her performance a concentrated consciousness of her multiple inner spaces, as well as and as much as to her external space – her body.

Veenapani Chawla, ‘Space and the Actor’, The Theatre of Veenapani Chawla, p. 118-119

As performers, we are – we become – able to create our own special performative presence, channel that energy to or through another (person or object), make the experience of space and time visible and visceral. It is the training and honing of our multidimensional consciousness that allows us to arrive at such a point, and take our audience with us. It makes us larger than life.

But what happens when this life is ebbing away?

You appear in snatches: sometimes in the depths of a focused gaze, in the tenacity with which you clutch my fingers or the hospital bed rail, in the habitual furrowing of your brow. But otherwise this body before me now seems uninhabited by anything but physical strain and pain. We check parameters repeatedly – blood pressure, temperature, oxygen saturation, pulse rate – all those markers of life. But where is the person who defined the life of this body? Your life now – if it can be called that - is a purely biological phenomenon. You have vanished: or, like a snail or crab, are able to recede so far into your home that we can no longer catch a glimpse of you. Or have you achieved the ability to leave and enter this home at your own will? Do you now already live around us rather than in the body I see before me?

Where is your life, Ma, and (why, how) does it still exist!

Ma Journal, 25 June 2022

The presence of your absence is palpable!

Leaving with grace / Left with Grace

16 October 2022

I return to writing this last section five days after you are gone, and I know I have seen you for the last time. My earlier notes for this segment have dwelt on the fragile beauty of flowers, the difficulty in defining grace, and aesthetic principles of performance that relate to both these intangibles. But now recalling your departure, I think of how easily you embraced fragility, grace, beauty, intangibility all at once in that last hour as you faded away, and how you retained the essence of all those over the last difficult years with a gentle graciousness that invited us to do the same. Thus, we sang to you, whispered to you as you left – which left us tranquil rather than bereft, allowing us to experience the rasa of sorrow in a detached, contemplative manner, rather than experience merely deep sadness and personal loss. So as I grieved, I was also able to ask myself – how does one find and offer grace, how does one find and offer Grace? – in the very moment that you found and offered both to me (again) for the very last time.

Your journey begins, as mine winds down -

Between the two of us, life flows on ||

Your lamp burns bright,

and you are surrounded by companionship

I am surrounded by darkness,

with the night stars for company ||

You stand on solid ground,

while I float in water

You may remain still,

I must move on ||

Your hands sustain [life]

[life] wilts in mine

But you are still fearful,

while I have left fear far behind ||

[translation is mine]

Yesterday, Ma – sitting in her chair and lucid before bed – reacted to this song. A memory, a recognition, a smile, a contentment.

Where she is now, she could have sung the last line to me quite truly.

It is bitter-sweet – for her to be there, for me to be here. And to be able to sing to each other – sometimes through words, sometimes melodies, sometimes silences – as she winds down as gracefully as she has always lived.

Ma Journal, 31 December 2021

For choreographers and dancers, the physicality and physical presence of bodily grace is a recurring concern. The words ‘physical’, ‘physicality’, ‘bodily’ sound strange in connection with a quality that is so incorporeal in itself, but finds expression through a corporeal presence. During the ‘Imagining Improvisation’ workshop in September 2016, my co-facilitator Anika Bendel urged us to refrain from using the word ‘grace’ as something definitive, because it is so personal, so much to do with the individual. Instead, to approach the idea/s of ‘grace’ as qualities of movement, presence, performance. We define it in so many ways: each form has its own principles of grace – what constitutes it, how one embodies it, how one communicates it, how one teaches it… if, indeed, grace can be taught! Or is it one of those things that is either inborn or imbibed?

-

An unlikely trio – my sister, dancer-choreographer Padmini Chettur, and I are having a conversation about dance. My sister confesses that she does not know much about dance, but one thing she does know is that dancers need to be graceful. Padmini rolls her eyes, looks at me and peremptorily asks me to educate my sister. All three of us laugh. But grace – the bone of contention – still lurks in the background, waiting to be understood.

-

The Government of India is celebrating 50 years of independence through the Swarna Samaroh festival performances all over the country featuring both upcoming and established artists. My guru – Smt. Rani Karnaa – is performing a solo kathak recital (after quite a long time) in Calcutta. I recall many impressions of the performance, but carry one clear memory that I know will return to me again and again. It is the third piece she is performing – a Kajri depticting a lovelorn nayika awaiting her beloved. She takes her place centre stage in darkness, a centre-spot fades in with the first strains of music to reveal her seated her head bowed, turned away from the audience – a recognisable pose for the role she is playing. She is wearing a flame coloured lehenga, with a green and red bandhni silk odhni. The audience is still a bit restive, still settling down after the break that the announcement between pieces has caused. The vocalist begins the first lines ad lib, and all my guru does is lift her head and gently twist her torso towards where the musicians are seated. The effect is electric: a hush descends on the audience. That one tiny (graceful?) turn pierces our collective consciousness, and says all there is to say about desire, love, loss, yearning… - we are in the presence of both grace and Grace. It is a fleeting, ephemeral, fragile moment – but it is the moment I carry with(in) me till today.

-

I am at the Swiss Dance Days in Zurich courtesy Pro Helvetia New Delhi, binging on Swiss contemporary dance. Two pieces remain etched in my memory: Le Récital des Postures by Yasmine Hugonnet and Antes by Guilherme Botelho. The first is a solo with practically no soundtrack at all apart from a short section where the performer vocalises; the second is an ensemble piece with 12 dancers set to a very present soundscape. The first is very quiet and introspective; the second is anything but. Both feature completely nude bodies: the first invites you to view it; the second demands that you do. The pieces could not be more different in aesthetic, but both are visceral experiences of grace, of power, of vulnerability, of the beautiful and painful fragility of our bodies.

All these moments are transitory in real time and space, but continually resonant in the time and space we carry with us. They carry the intangibility of transience, an ability to be both ephemeral and to linger, to die in the moment of living, to wither as one is blooming.

To establish a central concept of beauty, Zeami [the founder of Japanese Noh Theatre], chose to use the word hana, flower or blossom […] thereby creating a unique aesthetic theory for Noh. In his study and thought on hana he brings to light a causal relationship between the inner, expressive beauty of the performer and what is perceived outwardly as visual beauty by the audience; he includes in the idea of hana what is novel or interesting; and […] the Buddhist concept of mujokan, the impermanence and transience of all things, which sees the blossom as beautiful because it dies. Zeami’s theory is not an expression of a facile aesthetic consciousness that simplistically likens beauty to a flower; rather, it is an investigation into the true nature of beauty.

Komparu, ‘Three Stages of Beauty: Aesthetic Fulfillment in Noh’, Noh Theatre

Last year when the hollyhocks bloomed, you tore them from their stems and left them in my room. I think you wanted me to have them.

This year you have barely noticed them, though they look in at your window beaming every morning.

Ma Journal, 7 March 2022

SP pulled up the last hollyhock plants today before I could say goodbye to them – for me, for you. They bloomed beautifully till the very end, powered by your love and generosity. They will bloom again next year, and every year after – carrying the vibrant colours of your memory.

Ma Journal, 7 July 2022

Rõjaku (Quiet Beauty)

Rõ means old and jaku means tranquil and quiet; thus rõjaku can be thought of as the quiet beauty of old age. There are very few forms of theater that treat in as great a depth as the Noh does the inevitable aging of the human being.

The ultimate aged character is the old woman. […] These pieces are considered the most mysterious, profound and challenging in the Noh repertoire […] because of the permeating intent to seek ultimate beauty in state of kotan (refined simplicity), wabi (subdued elegance), and sabi (unadorned beauty), a kind of beauty that can be expressed by a flower blossoming on a withered bough.

Komparu, ‘Three Stages of Beauty: Aesthetic Fulfillment in Noh’, Noh Theatre

I think of the stholpoddo shrub (Hibiscus mutabilis) in our garden whose flowers bloom a milk-white early in the morning and then gradually blush into a deep pink over the course of the day. The pink then gradually turns to brown as the petals change from velvety to papery, finally disintegrating to dust. I think of the process of wilting, and the time it takes to wilt, the space it takes to wilt – it is so much more visible than the process of budding, of blooming. Do we notice erasure more than we notice birth?

Zeami answers the question, “What is hana?” thus: “After you master the secrets of all things and exhaust the possibilities of every device, the hana that never vanishes still remains”

Komparu, ‘Three Stages of Beauty: Aesthetic Fulfillment in Noh’, Noh Theatre

Kantor defines abstraction as

‘the absence of an object […] The ultimate essence of abstraction lies in this absence of an object; in the absence of a human body. It is as if we crossed the threshold of the [human] ability to see. It is as if invisible forces were players in an ancient tragedy. […] If something disappears, this does not mean that this ‘something’ dies out, but that it lives, moves, pulsates in a deeper [reality]’.

[quoted in Kobialka, Michal. “‘The Milano Lessons’ by Tadeusz Kantor: Introduction.” TDR (1988-), vol. 35, no. 4, 1991, pp. 136–47, https://doi.org/10.2307/1146169]

Next week on 22 October, I will dance for you. I will dance [a] disarmingly simple piece. It plays with space and time as only a kathak artist can – laying out time in space, and then filling it precisely, with care, with joy, with wonder, with gratitude for the opportunity to do so. And for the opportunity to share the creation of that jigsaw abstract world with an audience. We build worlds – that’s what we do!

I thought of only space and time and how they structure each other when I imagined this piece. But when I dance it for you, I will think of the foundations that are laid for us to stand on and build on / from. And how those foundations – like you – often become invisible [but can never vanish].

Ma Journal, 14 October 2022

6 November 2022

The morning after you left, people – more and more people – keep gathering around you to bid farewell, to be in your presence one last time. Because while you may be gone, you are still astonishingly present – silently drawing out tears, memories, and even laughter from all of us. There are many who have not met you for years, but carry you in their hearts, as you – in your capacity to embrace everyone – must have carried them in yours. We sit with you as the flowers collect around you, and soak in their fragrance – your fragrance. (“People are like fragrances” said VAH on her visit. “You can’t hold on to them.”) A soft smile plays on your lips, you look strangely refreshed, happy in our company.

We have wrapped you in one of your favourite saris to take with you, leaving all else behind. There you lie, still exuding and embodying the grace, beauty and gentle but solid serenity that drew – still draws – people to you. There you lie, resplendent in red. There you lie.

At peace.

At last.

Read this LAST

Listening to music together, I hand Ma a red felt pen and this notebook. She seems to have asked to do something, I feel she wishes to express herself. As the songs continue, she doodles slowly. I see shapes reminiscent of some Bangla alphabets – taw, thaw, haw… several versions of S, s, s… They may be something else to her entirely, but she keeps at it – doggedly, as is her nature. There is a beautiful, serene focus and unhurriedness. She takes her time, choosing pages, choosing areas. After about 15-20 minutes she chooses to stop. Hands me the pen, shuts the notebook. She has finished.

Ma Journal, 25 December 2021

Vikram Iyengar is an arts leader and connector based in Calcutta, India, and working internationally. He is a dancer-choreographer-director, curator-presenter, and arts researcher-writer. Co-founder and artistic director of Ranan Performance Collective, he also initiated and leads the Pickle Factory Dance Foundation – a hub for dance and movement practice and discourse. His scope of work spans practice, discourse, critique, ideation and management, and revolves around the central tenet of creating deep connections with and through the arts.

![Ki lekha ache [what is written here], I ask, pointing at her name on the flyleaf. Ma Shi… Shi… VI Shibani. Shibani ke [who is Shibani] Ma Aami [I am] VI Yes, Shibani Iyengar. She caresses the page as if feeling out h (5).png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5bbf29a011f784481d96c6e4/1671771902720-RQFBCTM9FSRUIZ0C71RG/Ki+lekha+ache+%5Bwhat+is+written+here%5D%2C+I+ask%2C+pointing+at+her+name+on+the+flyleaf.+Ma+Shi%E2%80%A6+Shi%E2%80%A6+VI+Shibani.+Shibani+ke+%5Bwho+is+Shibani%5D+Ma+Aami+%5BI+am%5D+VI+Yes%2C+Shibani+Iyengar.+She+caresses+the+page+as+if+feeling+out+h+%285%29.png)

![Ki lekha ache [what is written here], I ask, pointing at her name on the flyleaf. Ma Shi… Shi… VI Shibani. Shibani ke [who is Shibani] Ma Aami [I am] VI Yes, Shibani Iyengar. She caresses the page as if feeling out h (6).png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5bbf29a011f784481d96c6e4/1671771920457-1Z8O2QBL57MCBJ0FHREG/Ki+lekha+ache+%5Bwhat+is+written+here%5D%2C+I+ask%2C+pointing+at+her+name+on+the+flyleaf.+Ma+Shi%E2%80%A6+Shi%E2%80%A6+VI+Shibani.+Shibani+ke+%5Bwho+is+Shibani%5D+Ma+Aami+%5BI+am%5D+VI+Yes%2C+Shibani+Iyengar.+She+caresses+the+page+as+if+feeling+out+h+%286%29.png)